May 1st, 2017–

By stripping German Jews of their rights and livelihoods, the Nazi government sought to create a nation inhospitable to its Jewish population. In turn, they hoped to force emigration in an attempt to rid Germany of Jews. In response to this increasingly hostile environment, many German Jews did decide to flee the country. Because the government wanted Jews to leave, they reduced barriers to emigration. Doing so, however, did not mean the Third Reich allowed Jews to leave the country without any obstacles. While the government made it easier to emigrate, they also made it difficult for Jews to leave with any kind of wealth. Belongings, properties, businesses or practices, and financial assets often had to be relinquished or were heavily taxed. In turn, many Jews who emigrated left Germany with little to no wealth.

In addition to these obstacles, Jews leaving Germany struggled to find countries to take them in. Widespread anti-immigrant sentiments led many nations to impose restrictive immigration laws and quotas. Further, immigrants often faced difficult application processes. For example, Jews applying for U.S. visas needed to provide proof of U.S. sponsorship, had to complete extensive documentation in Germany, and needed to acquire a coveted number within the U.S.’s quota for German immigrants. These barriers coupled with slow methods of communication, financial hardships, and German hostilities made immigration a difficult feat.

Early on, many Jews migrated within Europe, hoping to escape Hitler’s reach. But as his power spread, the risk of staying in Europe grew. In 1938 Hitler annexed Austria, extending anti-Jewish legislation to this country and to the 185,000 Jews living there. After the planned violence of Kristallnacht in November of 1938, Jews in both Germany and Austria increased their efforts to leave Europe, resulting in a refugee crisis. In response to the crisis, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for an international conference to address Jewish refugees. In total, representatives from 32 nations attended the conference. Of these 32 countries, only one—the Dominican Republic—offered to take in additional refugees.

The Baermann family were some of the many Jews who emigrated from Germany between 1933 and 1940. Hilde, Resi, and Ruth grew up in Heisingen, Germany with their parents, Hermann and Rosalie Baermann. The family owned and operated two successful butcher businesses in the area, but in 1935, they were forced to relinquish these businesses and moved to Essen, Germany. While in Essen, the Baermann family decided to flee Germany. But because of the difficulties of immigration, each member of the family had to take a different route to make it out of the country.

Ruth was the first to leave. While living in Essen, Ruth met and married her husband, Herman Navon. Herman left Germany after being persecuted for previously dating Aryan women. Ruth followed her husband in 1937, joining him in Haifa, Israel.

Hilde remained in Essen and worked until she was able to gain passage out of Germany. In 1938 Hilde migrated to England where she worked as a domestic servant. While there, she married Eric Blumenthal. The couple decided to emigrate to the U.S. from the U.K., going through the extensive process to gain U.S. visas. Documents show Eric started this process on or before January 2, 1939, completing a number of character references, medical examinations, and consulate visits. He also had to give up much of his wealth to leave Germany.

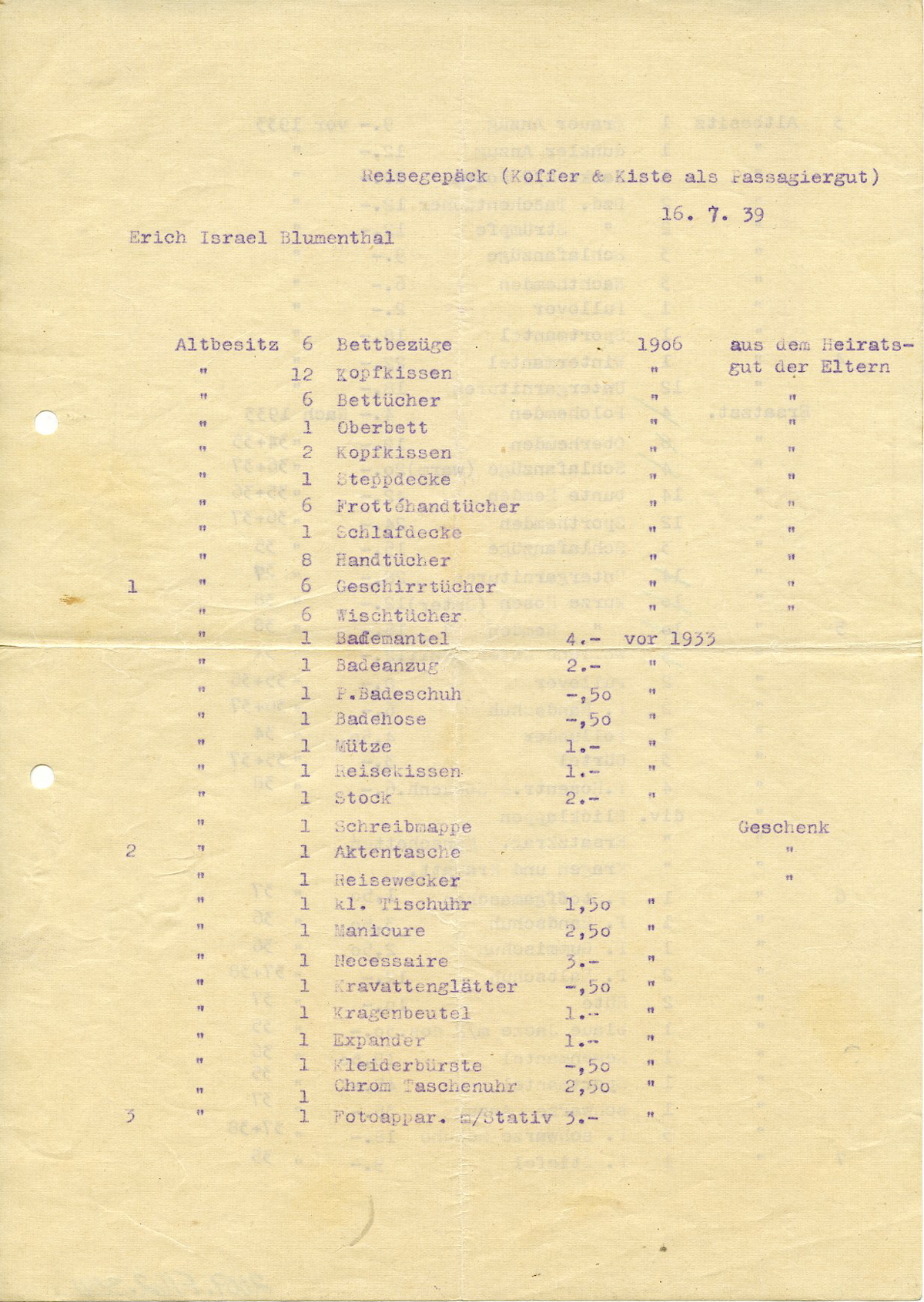

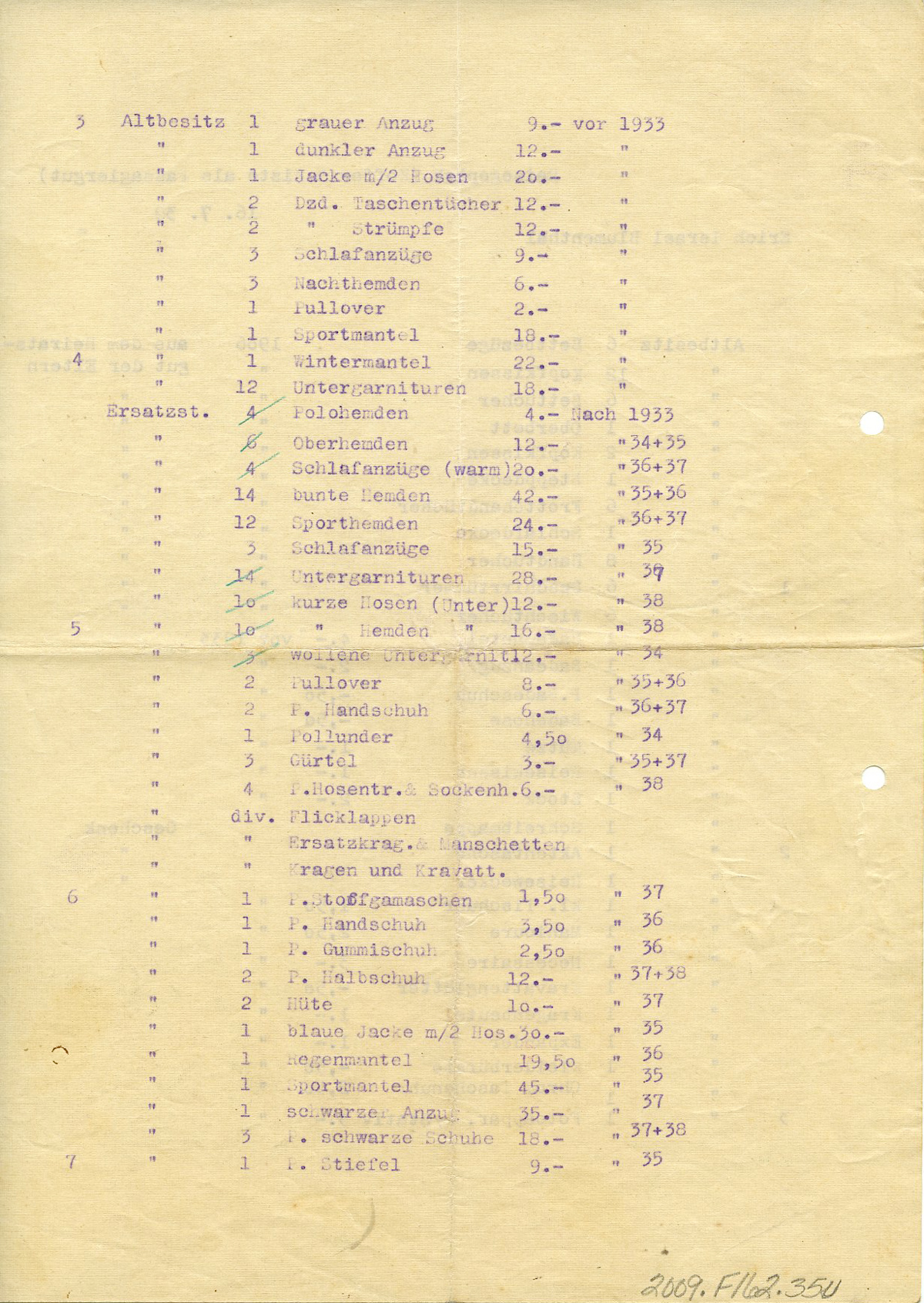

This packing list from the Baermann Family Papers outlines everything Eric Blumenthal had in his luggage when he left Europe. This list also includes an estimated value of each item, and where he acquired it. In a separate document, Eric had to declare that he was leaving Germany with nothing of significant monetary value.

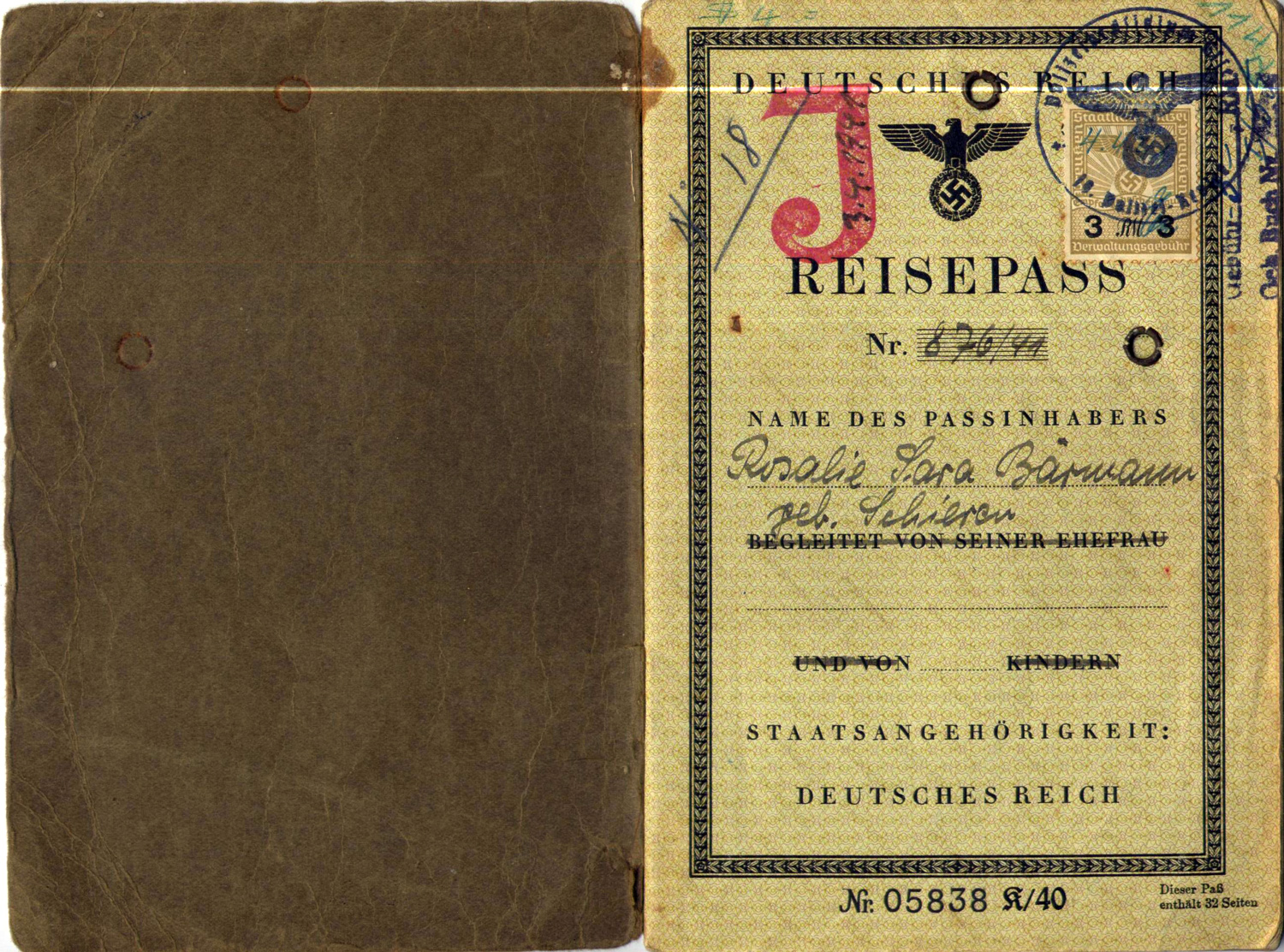

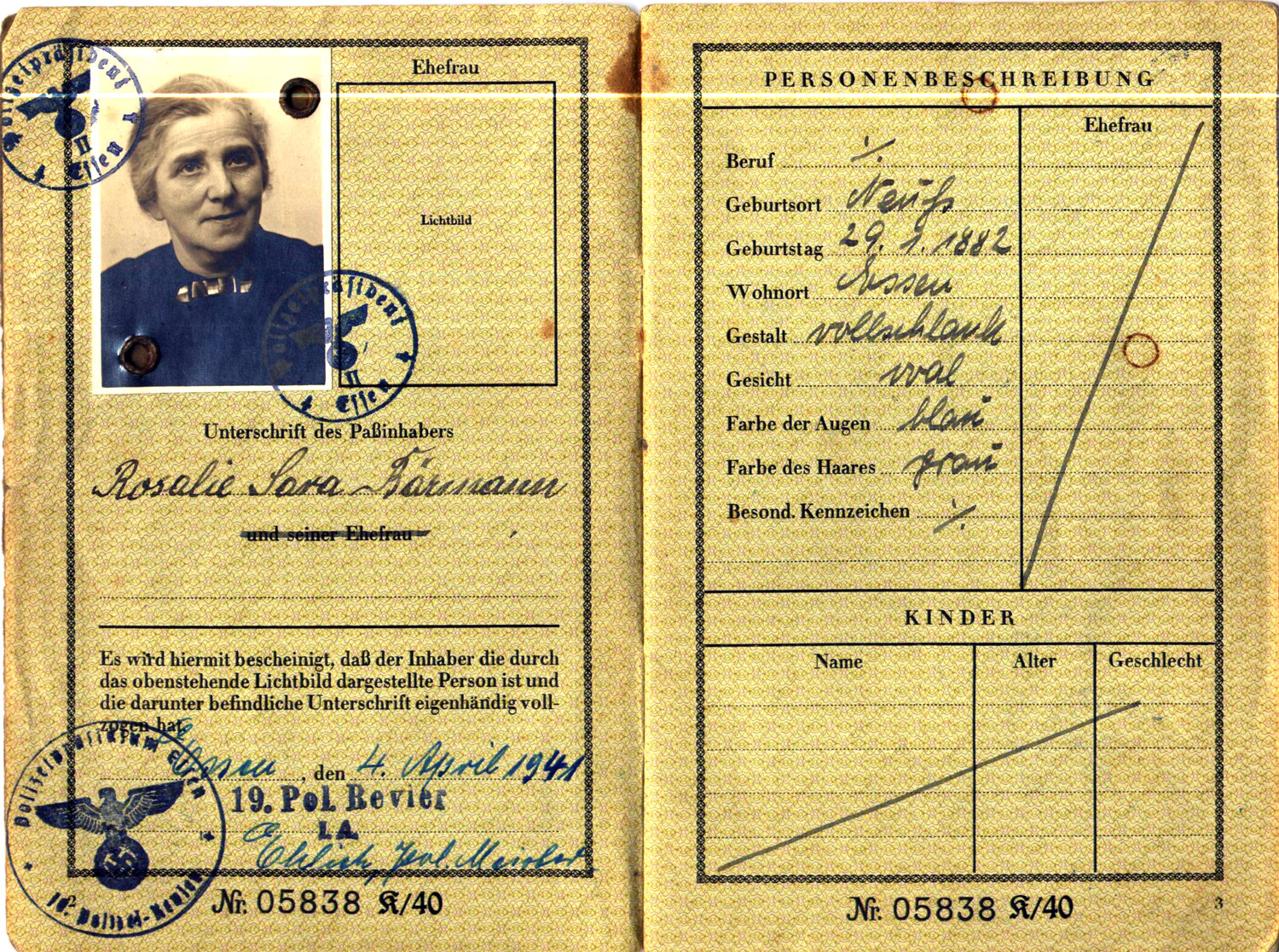

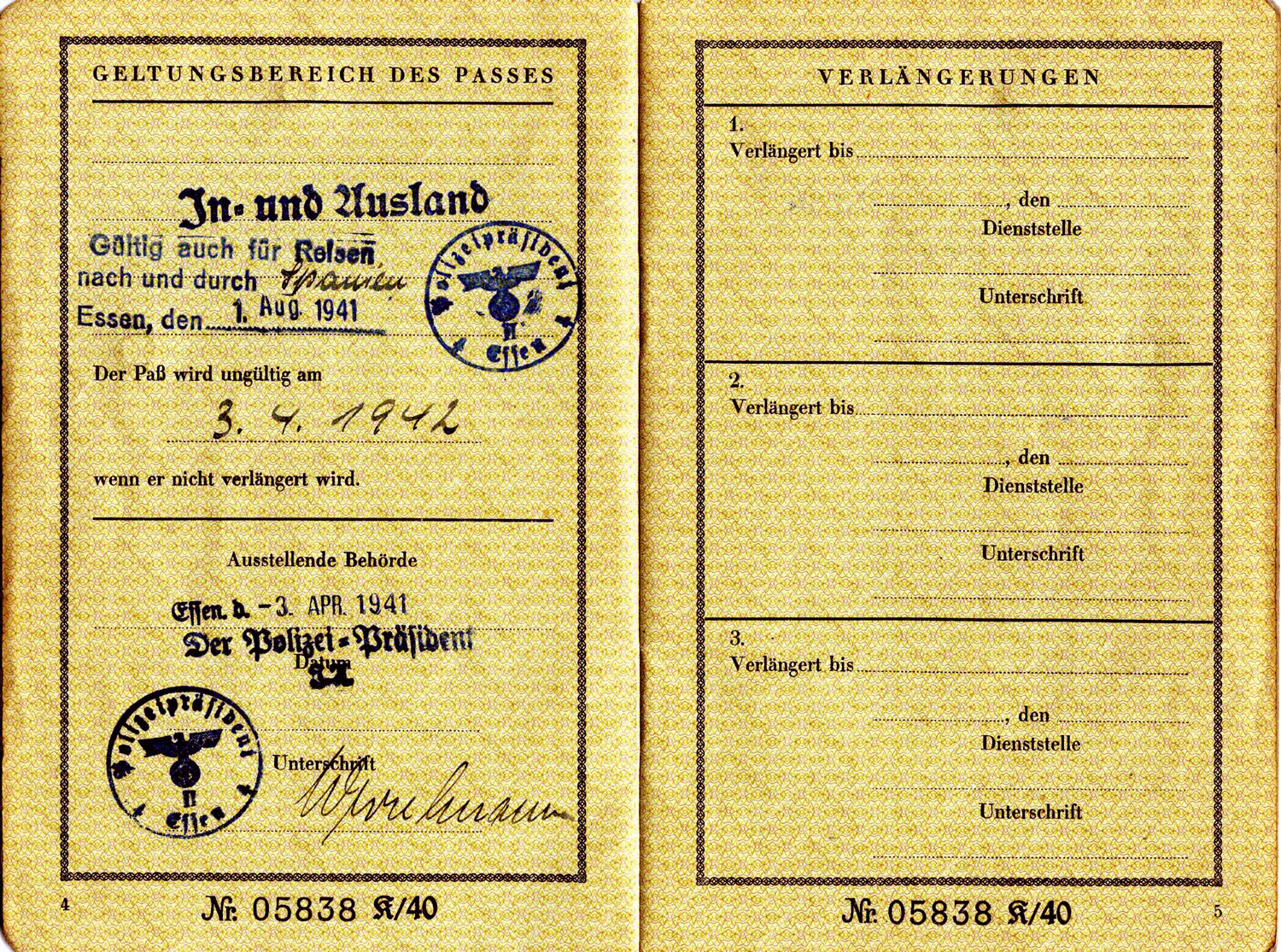

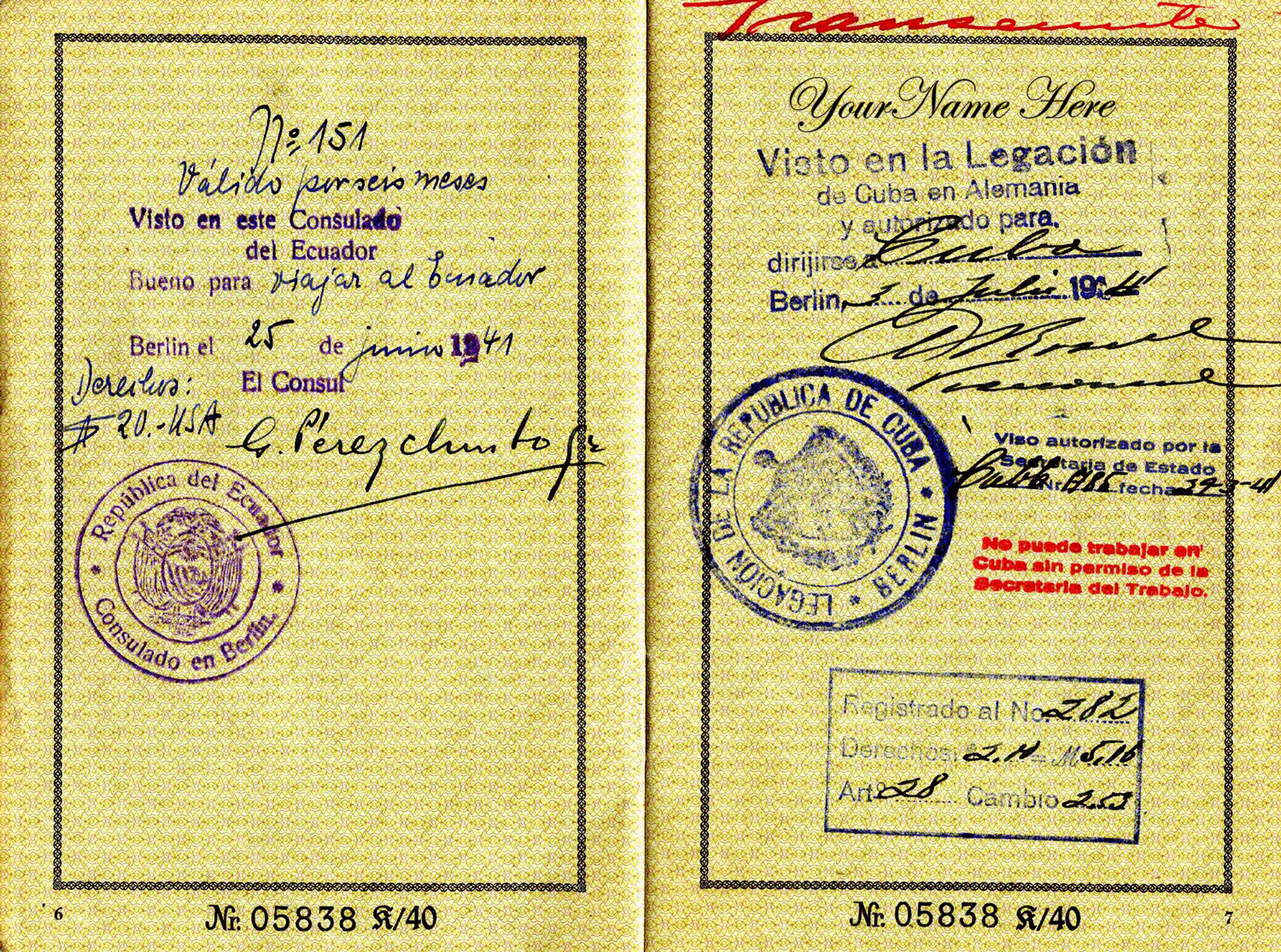

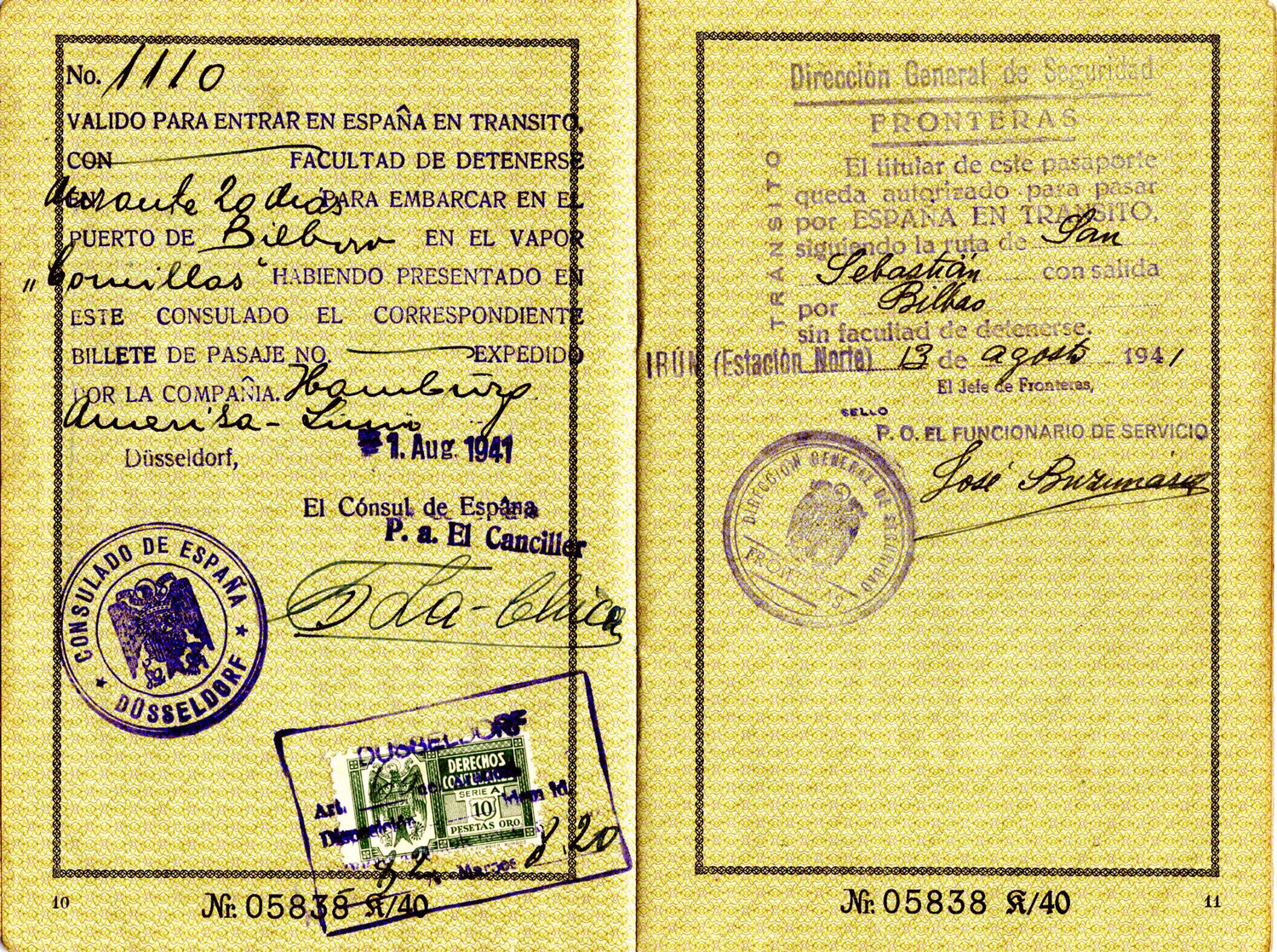

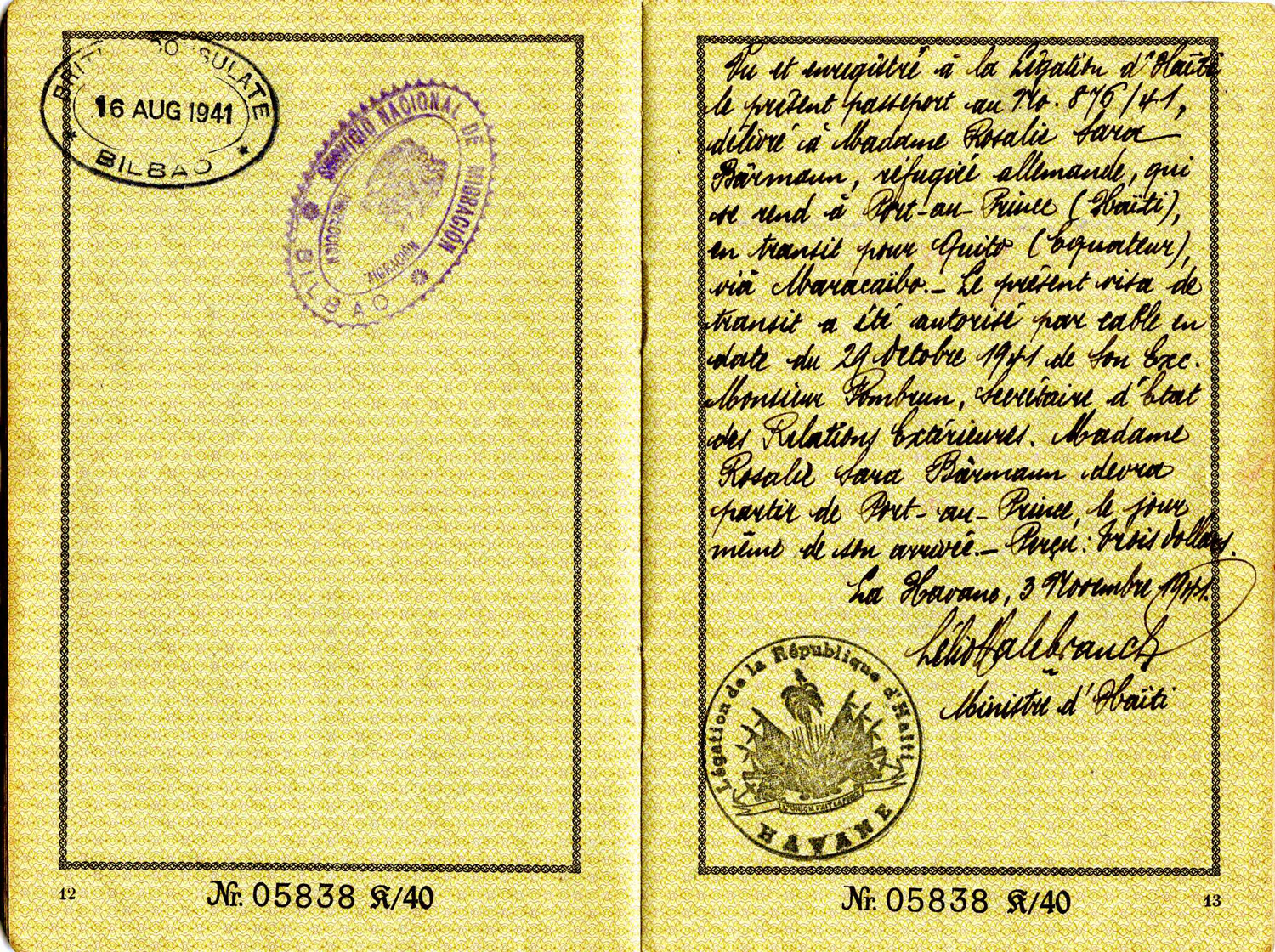

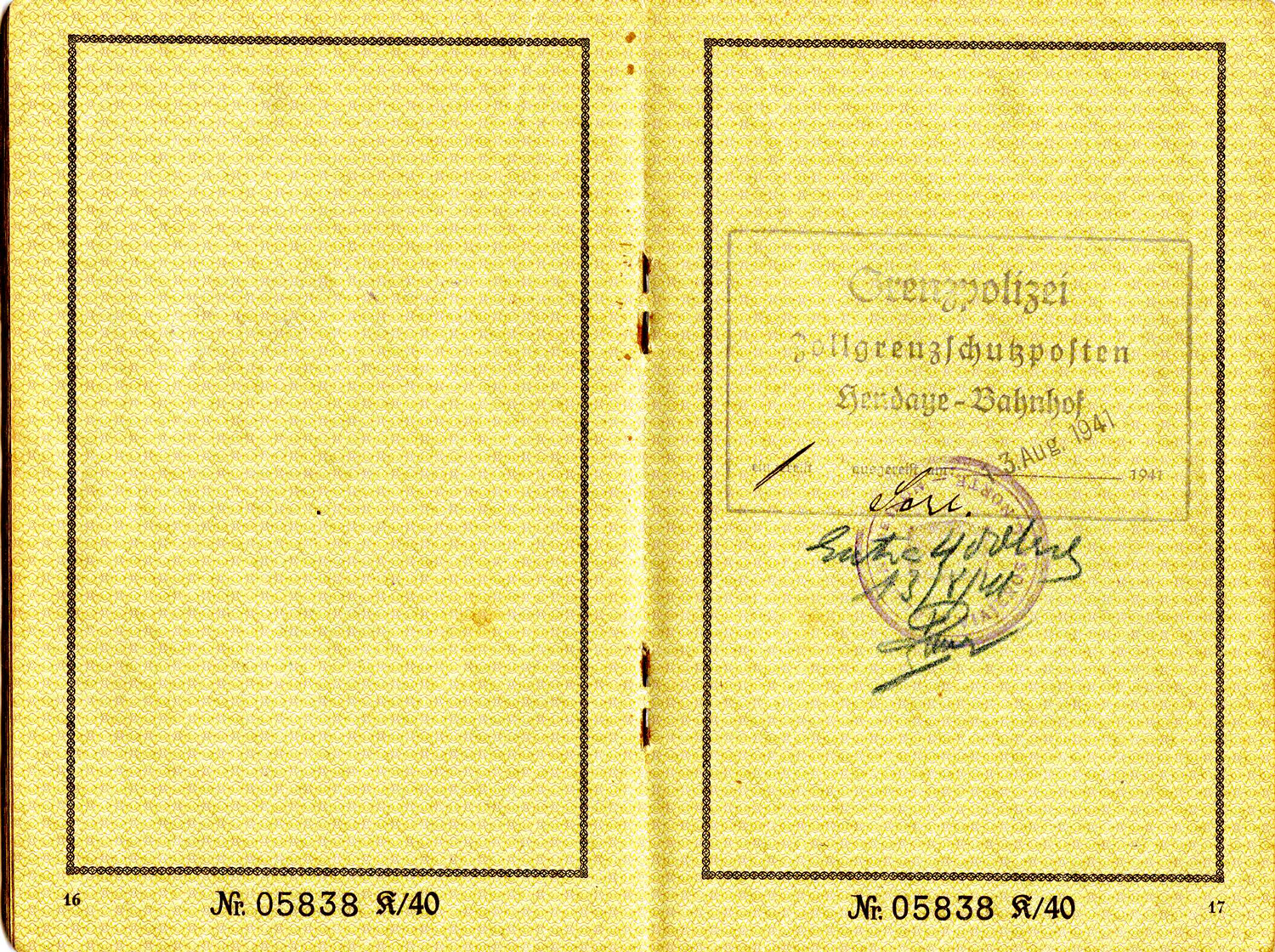

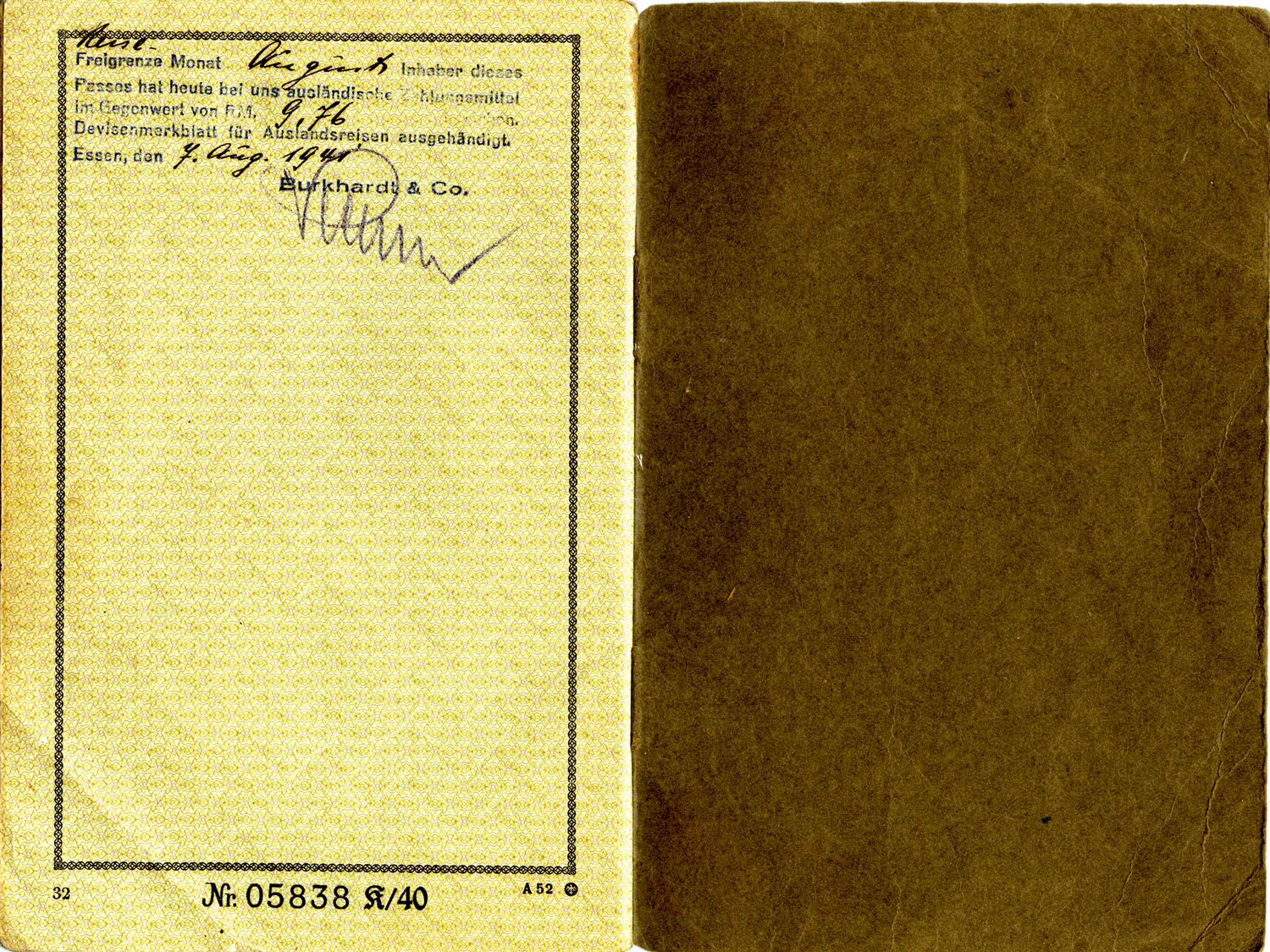

Resi, Hermann, and Rosalie all came to the states via Ecuador. After she left Essen, Resi went to Vienna before migrating to Quito. From there she was able to bring her parents to Ecuador via Havana. Rosalie’s and Hermann’s passports document their travels. Stamps in the passports are dated as follows:

- June 25, 1941: Ecuadorian Consulate in Berlin

- July 3, 1941: Cuban Consulate in Berlin

- August 1, 1941: Germany

- August 13, 1941: Spanish Consulate in Dusseldorf

- November 3, 1941: Columbian Consulate in Havana

- November 14, 1941: Ecuador

As indicated by these stamps, Rosalie and Hermann had to visit the Ecuadorian, Cuban, and Spanish Consulates while still in Germany to gain passage to each of these countries. In turn, they left Germany, and headed to Spain where they left Europe for Cuba. Once in Cuba, they visited the Haitian and Columbian consulates, possibly for travel or for backup visas. They finally arrived in Ecuador on November 14, 1941. The Baermann family was separated until 1953 when they reunited in the U.S., eventually settling in Richmond where they became U.S. Citizens.

282,000 German Jews made it out of Germany between 1933 and 1940. Many were able to do so because they had time to react to increasing violence in Europe. By the time the Third Reich entered World War II and reached Eastern Europe, where a majority of European Jews lived, it was nearly impossible for Jews to make it out of Europe.

The Baermann Family Papers and other objects in our collection are available to view online! Click here to view.